So, you’re considering doing a Class Play or you’ve started practices. Now, you’re wondering how evaluating drama will unfold. Or you’re wondering how to cast students or deal with irritation during rehearsals.

This post breaks down the class play into 5 actionable categories to give you confidence in your drama unit!

Drama in ELA: The Class Play

In this series, I’m going to share my experiences integrating Drama in ELA and producing a class play with my 9th grade English class.

Drama is so engaging for students, but is often put aside because it seems like a lot of work or doesn’t obviously correlate to higher test scores.

In this series, I’ll show you that Drama in ELA is not only possible, but beneficial to all students.

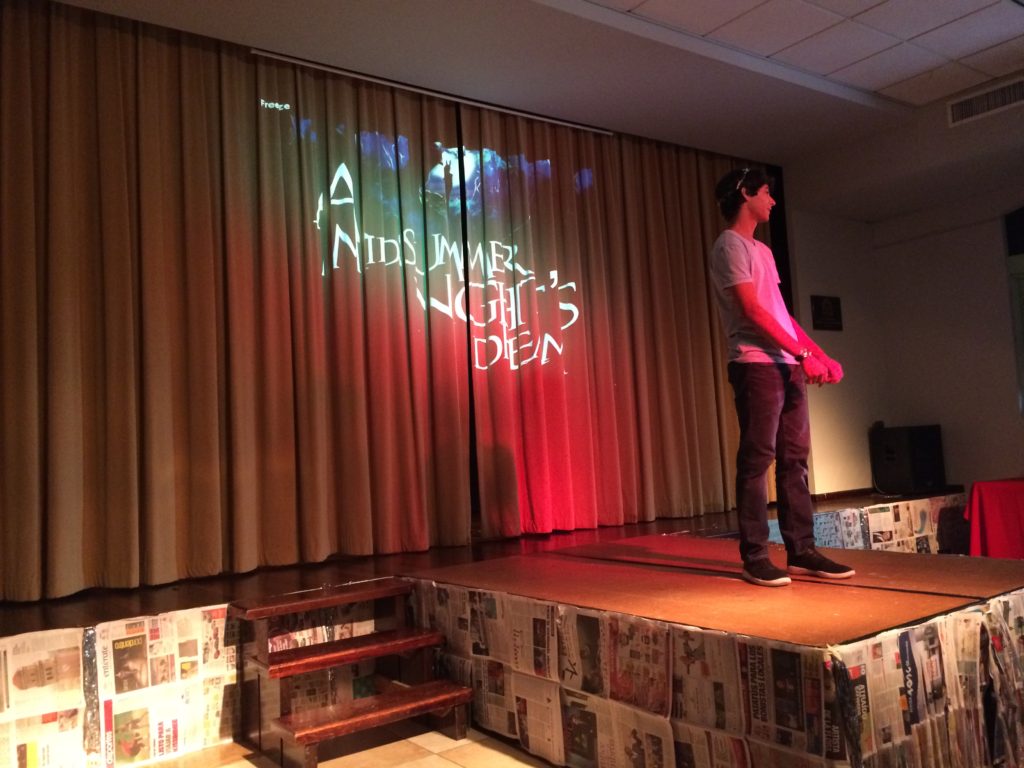

When I first had the idea to perform Shakespeare’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” with my two Honors classes, I knew it would be a challenge.

The students would have to buy into the idea. I’d have to structure in-class practices, but still give them enough freedom to engage creatively with the material. Most of all, we’d all have to work hard.

My first big hurdle was casting. My students read the play over Winter Break (the abridged version by Bob Gonzalez), came back and made a “wish list” of their top three parts.

Everyone wanted small parts.

This was a major blow to my confidence because I assumed that they weren’t interested in doing the play. Should I scrap the whole idea? Just move on?

I sat down with a colleague and she advised me that perhaps it wasn’t that the students were lazy, but that they were scared of failure.

After all, I’d told them that I wanted them to perform in front of the 7th and 8th graders, right? I’d turned up the heat.

The next day, I talked to my students and told them very honestly that my priority was that they engage with the play and that they make it their own – there was no “failure”, except not trying.

They submitted new wish lists and worked on audition monologues (major characters) and read-alouds (minor characters).

I made a spreadsheet of everyone’s wish lists and took the auditions into consideration. I had to combine two small classes to cast the play, a step which could be skipped at a larger school. I moved people around and looked and pondered and erased and drew arrows and finally managed to cast the show.

When you cast a Class Play, here are the takeaways:

- Dig deep and figure out why everyone wants a small part. It’s probably not laziness.

- Make students audition – either a memorized monologue of ten lines, or a rehearsed read-aloud from the play.

- Cast understudies. For our play, it’s the eight students in the smallest parts who are understudying for the eight biggest parts. This way, everyone is busy.

And not to spoil the end of this Class Play Adventure too much, but go ahead and cast understudies for every part if you can. You never know who’ll get mono or tear a ligament.

Now, I want to talk about developing basic drama skills. This will encourage engagement from all students, all the time.

This is something that I struggled with in the beginning, but I developed some tools to help my students.

If you’re like me, you LOVE the idea of students taking ownership of the class play, but you’re not sure how to help that happen without chaos breaking loose. They need to learn drama, too, especially if they’ve never been in a drama class or a school play.

How can you make this happen?

Give them the tools.

I structure the early practices of the class play with a series of mini-lessons and quizzes to build a common vocabulary and some basic competencies.

These fit into my goals as an English teacher, too, because they help students analyze plays as well as perform them. These mini-lessons and quizzes take about 10-15 minutes and they’re perfect for the first couple of weeks while students learn their lines.

- Drama Terms (monologue, scene, fourth wall, aside, etc.) – We go over these in class and practice some examples. You can find the list and quiz here, at my TpT store.

- Parts of the Stage – We cover the basic vocabulary (upstage, downstage, etc.) and do some “Simon Says” with stage directions. Here’s the PPT and interactive notebook plan for this mini-lesson.

- Blocking Notations – I make a list of 10-15 blocking notations that I want us to use in our rehearsals, including X (cross), DC/UC (down center/up center), and SL/SR (Stage Left/Stage Right). Students take a short quiz that includes “translating” both ways – notations to words and words to notations.

- Voice – This is an improvisation mini-lesson in which students adapt different voices and have us guess who they’re playing. I had students pick characters from our play, but they couldn’t choose their own. You can also design a mini-lesson with character stereotypes. Also, I take my class into the auditorium on this day and the rest of us sit in the back. It’s good projection practice.

- Levels – I teach students about the different levels of stage picture (Standing, Sitting, Kneeling, Lying Down, etc.) and we analyze a few movie stills to see how levels add to the story. Students are able to analyze power dynamics, intentions, and general visual interest.

The Lines Test

The sooner your students get “off book”, the better your practices will run. This is a class play, so part of students’ daily homework will be to memorize lines.

I share ways to memorize lines with my students, or better yet, I let the drama kids in the class share. Students can write out all of their lines, record themselves saying their lines, or just read through them a lot, but they’ve got to move those words from recognition to memory.

As soon as that happens, they activate synapses and the brain magic happens.

The way to hold their feet to the fire is a Lines Test. I give the minor characters a week, the mid-range characters two weeks, and the major characters two and a half weeks to memorize their lines.

As the students are practicing, pull them out one or two at a time (because you’ve got understudies, right?) and have them run a few random scenes. Don’t spend more than five minutes on this, and don’t take it too seriously – if they mess up a word or two, make them keep going.

Students will “get” that they need to work harder on memorizing, and acting is all about keeping going.

The last five minutes of every practice, my students fill out a Practice Log. This is meant to be a reflective space for them on their individual work, but also the work of the class.

The most important aspect of this is Goal Setting, in which they set concrete goals (memorize my second monologue, block the scene with Hermia) for the next practice.

We are in the last few days of rehearsal for our Spring Musical, and I’ve been thinking about irritation a lot. I’ve been getting and trying to reflect on what makes me so (INFJs for the win!).

I got home today from our big Saturday practice (9-3, phew!), and saw that Lisa and Jonathan from Created for Learning had just posted a video on the subject.

I figured there was no better time to slow down and share with you some of the lessons I’ve learned over the past couple months, and you can use this information to help your rehearsals run more smoothly.

In the end, irritation is our problem, not theirs, and we can take steps to resolve how we feel and help strengthen our relationships.

Irritation: Students talk or goof off during rehearsal. (Or, “Students who used to be so focused now talk and goof off during rehearsal!”)

So, I teach 9th grade, and this year, there’s been a huge upswing in 9th grade participation in Drama and the musical. I cast every upperclassman who tried out, and I still have 75% of my cast members who are 9th graders.

This whole “goofing off” thing hit me hard the other day, during a run-through. How was it that these calm, focused students that I see every day were now running around like monkeys when we had work to do?

I mean – there were spontaneous karaoke sessions happening every time the tech crew had a question. I was so frustrated and tired from a looong school day, and we’d already been rehearsing for an hour, and couldn’t they just focus already?

Riiight.

You asked them to come out for the musical and expand their horizons, and look – they did! For many of these students, this is their first show.

They are discovering this new creative and sometimes goofy side to themselves! This is what I wanted, right? This is the goal of drama, right?

Also, are you tired? They’re tired too! I also realized that my students, like me, need a break. I actually solved this one the next day by asking a parent to bring in snacks for a scheduled break time.

I even threw on some music for an impromptu dance party. It only lasted 10 minutes, but it was enough for them to relax for a bit and get back on track. The rest of the rehearsal went off without a hitch.

Irritation: Students don’t know their lines or their lyrics

This is a common frustration for directors, and it seems so obvious that this is the first step an actor needs to take in successfully executing his or her part.

However, as I considered my students who fell into this category, I began to realize something.

Some students didn’t know how to memorize. When I asked them, they shared that they would read the text over and over, but that they still weren’t learning.

I showed them how to go line by line, then paragraph by paragraph, until they got their parts down.

Irritation: Students don’t exit correctly / aren’t quiet backstage / don’t cheat out to the audience / don’t look expressive when they don’t have lines

So you have a few talented students, those who naturally find the light and engage the audience. How about the rest? What aren’t they getting?

They probably have no idea what “correct” looks like. Just as we do in the classroom, we need to model for our students. What does a successful exit look like? What does “cheating out” mean? I have a young cast, as I mentioned, so these questions are even more important!

I have solved many problems over the course of the last few days by photographing or taping the scene, and showing students what’s happening.

They are still developing the empathy and awareness necessary for actors to imagine what the audience is seeing. Another great trick is to pull students out one-by-one to hear what the audience can hear from backstage (and, as all directors know, the answer is everything!).

In closing…

It’s easy to forget that your musical cast is composed of students, but rehearsal is really just another classroom.

I’ve discovered over the last couple of months (and intensely in the last few days) that my problems can usually be solved by employing a few techniques from the classroom:

- Empathy – Make it social. Kids will be kids. High schoolers are not professionals, they’re not getting paid, and they’re just as tired as we are. Give them breaks and let them have fun.

- Scaffolding – Break major tasks (learning lines, learning blocking) into smaller chunks and show them how to accomplish a chunk.

- Modeling – Set your expectations (for speedy exits, backstage noise level, transitions between numbers) and model them. Show your students what you mean when you name the parts of the stage or a blocking term. Help your students build these foundational skills that they need to be successful.

Now, let’s talk about the best part of doing a class play: the performance!

This is the fourth part of my class play series, so be sure to check out the posts on Logistics & Prep, Filling Their Toolkit, and Evaluation Ideas.

We had two performances of our class play, and this was a good amount for amateur student actors.

Parents’ Night

Our first performance was a final dress rehearsal in front of parents. I reached out at the beginning of our rehearsals to let parents know that this would be happening, and the turnout was amazing!

Students were in full costume and it was supposed to be a “real show.” Most of my students rose to the occasion, but a couple of them really struggled to remember lines under the performance pressure.

I thought the biggest challenge of Parents’ Night would be that it was in the evening, and this was a “class play”. A couple of my students had to forego an evening game, but it turned out that most of them were available.

I had several cast members in the Spring Musical, too, and they told me they wanted to have a regular after-school practice before the Parents’ Night for the class play.

Middle School Performance

Our school is a combination middle and high school, so we invited the middle-schoolers to see our final show. My students (9th graders) did not want to perform for older students, but were willing and excited to perform for the younger ones.

My other two 9th grade classes came, so the performance also benefited their own study of A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

It’s a good idea for a younger crowd to have one of your students give a quick summary of the exposition. This helps them establish some background, and they can catch onto the plot more quickly.

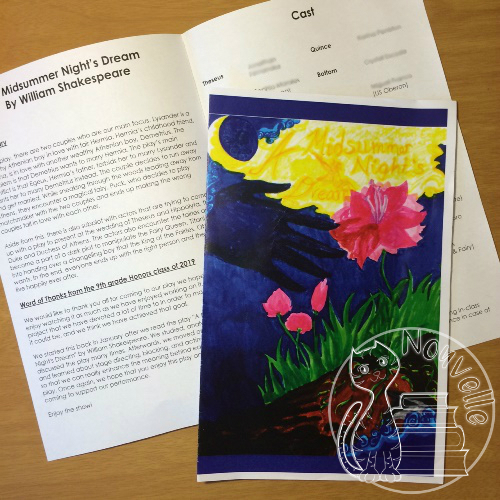

We also printed a summary in the program. Whereas I printed color programs for the parents, I did black and white for the middle schoolers, and had them share one for every 2-3 students.

The school filmed this show, and was able to release DVDs to the parents. You may or may not be able to do this, depending on the rights of your play. Since we did Shakespeare, it’s in the public domain.

What Comes Next for the Class Play?

Well, we ended our run there because of some testing that we had the following week, but we were invited to come perform for a local elementary school. This would have been another beneficial opportunity, but we just couldn’t manage it.

We did spend an extra class period watching the show, which is a great way to relax and reflect before beginning a new unit.

My Honors students said that the class play was the highlight of their year in English, and they could quote lines from the show all year long. It was a large time commitment, but very worth it.

Blocking, becomes more and more important as the practices continue. Once students are “off-book” (memorized), they need places to go on the stage.

Young actors need to know that blocking is part of building consistency as an actor. Your fellow cast members need to be able to count on you to arrive at a certain spot at a certain time.

One of our biggest blocking challenges in A Midsummer Night’s Dream was the Catfight. Getting all four actors to get from point A to point B in the same amount of time, every time, required planning.

Still, once students know that blocking creates safety on the stage, the magic happens – Hermia lunges at Helena, only to be pulled back by the boys, and the audience gasps in appreciation!

Understudies, Input, and Saving the Day!

I told you at the beginning of this adventure that I cast understudies for every single part in the play.

Part of this was out of necessity – I had two classes working on this project together, so I needed Hermia in one class and her understudy in the other so that all of the actors could work productively during class.

For the other part, I wanted students to give constant input. The understudy system meant that two people felt invested in every role, and felt that they could make suggestions.

This worked out beautifully for us, and the input of understudies made two of the woods scenes so much more interesting.

Then, a week before the show, my lead fairy (you know, the one who has a monologue and mocks Puck?) tore a ligament. Ouch! Luckily, the understudy was ready to go, and she was amazing!

Three days before the show, Flute got mono and couldn’t perform. His understudy stepped up in a major way and even memorized his lines by the time they performed for the middle school!

The night of the Parent Performance, Quince just didn’t show up, and the understudy (who was also Egeus) had to go on.

Hooray for these stellar understudies! They knew the motto: the show must go on!

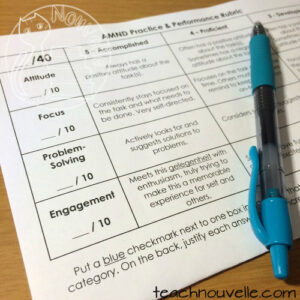

Accounting for Soft Skills when Evaluating Drama

A big question my teacher friends asked when they heard what I was doing was how I was evaluating drama in the ELA classroom.

My students worked on this play for four weeks of class time, so how did I keep the gradebook up-to-date?

I split the evaluation into three parts:

- Objective grading of vocabulary, blocking, and parts of the stage quizzes

- Semi-subjective grading of practice logs (largely focused on grading ideas and content) and lines test

- Subjective assessment of student reflection on soft skills.

I distributed a rubric with descriptors about attitude, focus, problem-solving, and engagement. As they wrapped up practices and performances, students had to self-assess, writing justifications for each score using concrete examples.

For example, to get a “10” on problem-solving, a student had to describe a problem that s/he actually solved. This rubric made evaluating drama in the classroom much easier, and students began reflecting on the process.

Whatever grading strategy you use, make sure that your students know how it’s going to work before starting rehearsals. My students need to know that they are expected to solve their own problems, and we have to brainstorm what focus looks like.

That’s it for evaluating drama in the ELA classroom!

2 Comments

Building Drama Know-How in ELA - Nouvelle by Danielle

August 16, 2016 at 1:42 pm[…] Evaluating Drama in the ELA Classroom […]

Class Play: A Successful Show - Nouvelle ELA Teaching Resources

May 30, 2017 at 9:01 am[…] Now, let’s talk about the best part of doing a class play: the performance! This is the fourth part of my class play series, so be sure to check out the posts on Logistics & Prep, Filling Their Toolkit, and Evaluation Ideas. […]